The Pillars of Monetary Economics

Monetary Realism

Monetary realism states that money is real, it matters, and it shapes the dynamics of the economy. If we want to understand the economy, we have to study how money actually works in practice. Ignoring or abstracting away from money—as neoclassical economics tends to do—hinders our understanding of the economy. Money is not a mere veil that hides the true nature of exchange. It is not merely a medium of exchange. The nature of money shapes the dynamics of the economy.

Banks, likewise, are not merely financial intermediaries simply facilitating payment; they create markets. Introducing new purchasing power into the economy via expanding both sides of its balance sheets creates new markets that otherwise would not have been created. This enables the mobilisation of resources for use in the economy that otherwise wouldn't be mobilised.

However, finance becomes self-indulgent. Finance becomes a tool for mobilising more financial resources. In moderation, such activity is beneficial. New financial markets that promote more cost effective selling or buying of products from/to abroad facilitates profitable trade. This can enhance the material welfare of societies as a whole. In excess, on the other hand, financial activity is pursued for merely its own sake of attaining a profit without any recourse of whether such activity benefits society as a whole. Worse, such activity can become extractive hurting society distributing wealth and resources to finance rather than finance being used as tool for creating new wealth.

We call this rentier speculation—profiteering purely for the sake of profiteering by manipulating resources rather than creating new economic value. Rentier speculation is by no means limited to financial speculation. Any form of extractive economic activity involves rent seeking.

Private individuals can rent-seek by monopolising land forcing others to pay them for the liberty of exercising their liberty for having a constant place of residence. Companies and states can use control over natural resources, like grain or oil, to extract benefits from other individuals or other states. The Russian kleptocratic state rent seeks by extracting value from the proceeds of selling natural gas and oil without widely dispersing such wealth to either Russians or the rest of the world.

One of the original definitions of capitalism focussed on how the Netherlands dictated trade terms and utilised its financial power in dominating the newly formed Belgian state in the 19th century. Democratically controlled states can also engage in rent-seeking, whether by extracting resources from other communities or from marginalized groups within society who lack power to resist majority will.

Monetary realism is not a doctrine about what money is, but a method for analysing the economy. Rather than marginalise the importance of money, its centrality to enabling economic activity and other social activities is a pillar of our economic paradigm. Money is a social technology, and like all technologies, innovations occur. Over time, these innovations can become so profound that previous paradigms become irrelevant.

"Ipsa scientia potestas est." – Francis Bacon.

Once we have knowledge of how money works, we can adapt the social technology for our own social purposes. Such innovations cannot be implemented at will. What should be clear now is the role that market, institutional and political factors impact the development of how money originated and what we can do with it.

The Hierarchy of Money

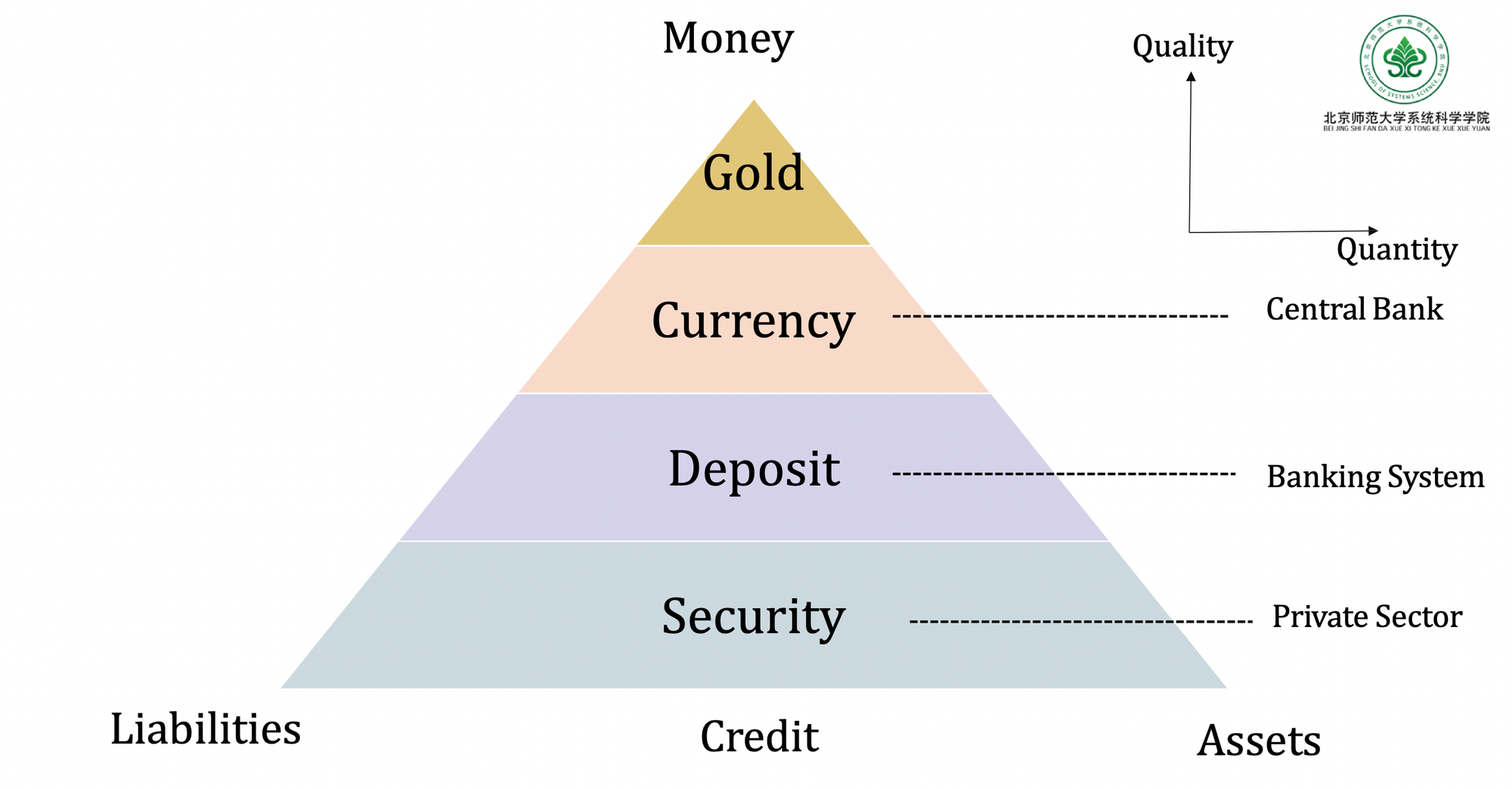

At its core, the monetary world is hierarchical. Money is an IOU—a promise to settle a payment. But not all promises are equal. Who decides whether a payment has truly been settled? In theory, everyone does. In practice, some promises carry more weight than others. Some actors issue promises the market trusts more than others. Some money is better than other money.

During financial booms, private securities may be treated as money. People accept them as settlement because they believe they can easily resell them—often at a profit. We call this liquidity. The more liquid an asset is, the more readily it can be exchanged.

In periods of confidence, even speculative securities can function as money. But when the bubble bursts, trust evaporates and people seek money that's higher up in the hierarchy, whether they be deposits, currency, or central bank reserves. Those same securities become recognised for what they are—credit, not money. The willingness to accept them disappears.

This reveals a deeper truth: whether a form of credit becomes money depends on trust, where one is situated in the hierarchy of money, market dynamics, and liquidity. The more secure and trusted the IOU, the closer it is to functioning as true money. In prosperous times, the boundary between money and credit blurs. "Money is credit. Credit is money." But this is only true under optimistic conditions—the so-called animal spirits of financial markets.

In more cautious or “sober” periods, distinctions resurface. Markets only treat secure, credible credit as money. Some IOUs are too risky to be trusted as means of payment. The hierarchy becomes visible again.

In times of crisis, the split becomes undeniable. Central banks issue the highest form of money in the system—cash and reserves backed by state power and institutional trust. Meanwhile, bank deposits—normally treated as money—can lose credibility. We realise they are, in fact, private promises. If those promises are doubted, they’re treated as what they really are: unsecured credit.

At par, £1,000 in a deposit should equal £1,000 in cash. But under stress, this equivalence breaks down. We trust the Bank of England more than we trust Barclays. We trust Barclays more than we trust hedge funds or crypto platforms. This qualitative difference—how trustworthy the issuer is—forms the basis of the hierarchy of money.

Some money is more trustworthy than other money. Some credit is more credible than other credit. This is not just a technicality—it shapes how the monetary system functions in practice. At the top sit central bank reserves and currency, the most secure forms of money. Below that are commercial bank deposits, then money market instruments, and further down, various types of private credit. The system is layered—each layer relying on the credibility of the one above. The system and hierarchy is non-linear as well. This layered system doesn't just affect institutions—it shapes everyday behaviour, especially in how people choose which money to spend or save.

Crucially, the best money is scarce, and the worst money is abundant. 'Notes and coin' represent a small fraction of the UK money supply. Central bank reserves are limited and used mostly between financial institutions. Yet commercial bank deposits—less secure, privately issued—make up the vast majority (around 96%) of the money in circulation. The hierarchy isn’t just conceptual—it’s structural.

This reality is captured in Gresham’s Law, which states that "bad money drives out good money." When two forms of money circulate at the same nominal value but differ in perceived quality, people hoard the ‘good’ and spend the ‘bad.’ Why hand over something you trust when you can get rid of something you don’t? The result: high-quality money vanishes from circulation while the lower-quality money remains.

Gresham’s Law reflects the hierarchy in motion. If a system flooded itself with only good money, it would debase that money’s quality—often through inflation, eroding its real value. This would be true even if there was no increase in the money supply. This interplay of trust, liquidity, and hierarchy shapes the entire monetary system. Money, at its core, is not just a number. It is a claim, and the credibility of that claim depends on who is making the promise. And that credibility—the invisible architecture of finance—is what holds the entire system together, or lets it collapse.

The Four Prices of Money

Perry Mehrling, in his course The Economics of Money and Banking, states that there are four prices of money in the economy. All these are key for both understanding money at the macroeconomic scale and the financial system itself.

Coursera

Coursera

Par

All money in a given denomination should be priced the same. £5 in banknotes should be equivalent to £5 in bank deposits. There should be no difference between the price of currency and the price of a demand deposit. Monetary economists refer to this as the price of par – the price of money in terms of other money.

Par is vital for the stability and viability of monetary systems. I cannot trust a money system if I don’t know whether I could gain or lose money simply by exchanging money with others. I must trust that £5 deposits for me also means the same for another person. Further, I will be less inclined to trade and exchange money if the price of it differs depending on location.

The power of par is that we can treat demand deposits from a bank as if they were currency. If they are priced the same, then we can easily convert one for the other. This helps provide liquidity to the system. There is this 'illusion' blurring the distinction between currency and the demand deposit. This illusion is integral for a well functioning financial system.

During financial crises, when the system is under strain, par can cease to exist. For instance, during a bank run people panic fearing they won’t be able to retrieve all the money in their deposit accounts. Consequently, they demand their deposits be converted to currency. However, the amount of currency circulating in the economy is significantly smaller than the amount of demand deposits circulating. There is no way in which everyone can convert demand deposits into currency with each priced at a 1:1 ratio. Par has been violated.

For example, suppose you request £1 million in deposits during a bank run. In the UK, the bank will only guarantee your deposits up to £75k. So if you only receive £75k, then par has essentially been violated.

Without par, modern financial systems would be impossible or more cumbersome than now.

Interest

Interest is the price of money in terms of future money, effectively acting as the cost of deferring payment. It is the price that comes with banks using their exceptional tool of increasing both sides of its balances sheets, thereby creating new monetary circuits and new purchasing power in the economy.

Interest acts a source of profit for financial institutions engaging in lending activities. The rate of profitability that banks earn from lending helps regulates both demand and supply for credit. Monetary policy by the central bank plays a pivotal role in influencing the profitability and financial sustainability of banks, thereby manipulating the supply and demand or credit both directly, via setting interest rates, and indirectly, via providing liquidity for banks in its day-to-day operations.

This price of money, however, also entails a systemic bias towards continual growth and expansion, as the late Bernard Lietaer eloquently points in the presentation below. When credit is issued, we essentially are using future purchasing power in the present. Purchasing power in the future must be created so that interest can be paid off, requiring the constant creation of new credit. However, credit won't be created for settling credit. The sustainability of the continual expansion of credit requires the extraction and manipulation of resources for profit, which in turn creates the demand for credit needed or sustaining interest. The consequence is a system that necessitates growth for its own sustainability. In the long term, the irony can't be lost that such perpetual growth that sustains the system is unsustainable.

Bernard Lietaer giving a presentation about monetary reforms allowing for a more sustainable economy

The result is a self-reinforcing cycle of debt-driven expansion that accelerates ecological breakdown and contributes to the ongoing collapse of Earth’s biodiversity. Even though it would be an exaggeration to blame interest as the primary culprit for this biocide, it plays an important role in ensuring the system must perpetually seek ecologically unsustainable extraction of resources and the destruction of the biosphere.

We also see this requirement for growth in the housing market. Increasing 'house' prices becomes necessary so people remain solvent while paying off the mortgage and its associated interest. Without increasing house prices, the balance sheets of many individuals would have little net worth making them extremely vulnerable to becoming insolvent, i.e. negative equity, which would suppress demand and risk opening the economy to a debt deflation trap. Debt deflation is where paying of the debt actually increases your debt burden because the value of your money, your purchasing power, your assets reduces faster than the reduction in your liabilities.

In fact, it is not the price of a house per se that actually increases. It is the price of land that increases. Owning land becomes more valuable because it is what the financial systems leverages its lending on. This is the primary driving force for rentier speculation in Western economies - land speculation. This is a primary driver for the cost of living crisis in the UK. Housing costs are becoming increasingly unaffordable for youth. Credit fuelled land speculation in the past and present is destroying the futures of today's youth, which will only destabilise our economies and societies for years to come.

An analysis by Positive Money shows that most lending occurs for purchasing existing assets, especially real estate. The analysis suggests 54% of lending is for mortgages, rather than for productive enterprises that will generate wealth for the future. Financial intermediation industries also have seen a significant chunk of lending directed at them.

PositiveMoneyAlec Haglund

PositiveMoneyAlec Haglund

Exchange Rates

Exchange rates represent the price of money in terms of other denominations of money, e.g., the value of the pound sterling (£) in relation to the US dollar ($). This is the domain of foreign exchange (forex) markets.

Exchange rates impact the costs to and from individuals, organisations, and states buying and selling goods internationally. A favourable exchange rate can make trade cheaper, stimulating economic activity, while an unfavourable rate can make trade more expensive, discouraging it. Highly volatile exchange markets are beneficial for short-term speculative trading but detrimental for those seeking stable, long-term trade relationships.

Central banks will buy and sell foreign reserve currencies to influence the forex markets, maintaining domestic price stability. Such actions, though purposeful, should be subtle, ensuring that stability is achieved without disrupting the natural flow of economic forces. When states start competing against once another more aggressive manipulation of exchange rates can be used to try dominate other countries or leverage a significant advantage over national economies.

Price-level

The price-level is the price of money in terms of commodities. What can a unit of money buy for you? The higher the price-level, the more money is required for buying a particular set of commodities. The lower the price-level, the less money is required buying commodities. When the price-level increases, we call that inflation. When it decreases, we call that deflation.

In theory, deflation sounds all well and good. Needing less money to buy purchases sounds great. If all money was outside-money, then the sentiment would be a fair one. Except, we live in a system dominated by inside-money. What's money for one person is a liability for another. The problem with deflation is that the amount of monetary assets reduces, but the liabilities don't. We become insolvent. What's worse is that by reducing the amount of money available, there is far less liquidity in the system. This actually makes it far more likely you won't pay off your liabilities on time, not satisfying what Perry Mehrling calls the survival constraint, resulting in bankruptcy. This process is what we call debt deflation.

Our systems instead rely on a steady but perpetually increment of the price-level. This mild inflationary tendency does the precise opposite of debt deflation. It gradually increases the nominal asset price of money, while liabilities remain unchanged. It makes debt obligations created now less burdensome in the future. The downside is a steady decrease in the purchasing power of money, however this only becomes noticeable over long periods of time ensuring political and economic stability in the present.

Economists and politicians are principally troubled with either inflationary shocks, stagnation, or hyperinflationary tendencies. Inflationary shocks are when prices for some, or all, commodities increase dramatically. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the price of grain shot up increasing food prices. Likewise, the cost for natural gas and oil shot up increasing energy costs. Given the central importance of energy for productive activity, higher energy costs entails higher costs for all economic activity hurting profitability, growth potential, and, consequently, the sustainability of our economic system.

Now we can start seeing how these seemingly innocuous prices of money play a fundamental part in our economies. The breakdown of par entails the breakdown of the entire financial system. Interest creates dynamical forces forcing us into the unsustainable growth of both credit and resource extraction. Exchange rates are tools by which national economies leverage itself against other national economies - dominating or even rent seeking from other national economies. The price-level impacts overall costs and as a result the sustainability of credit issuance - the lifeblood of the economy.

The Quantity Theory of Money

American economist Irving Fischer developed the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) which supposes that increases in the money supply causes increases in the price-level. Conservative economists use the logic of QTM to question the wisdom of sustained government spending. The accusation is sustained government system increase the money supply thereby causing inflation while crowding out private interest. The problem with the theory is that it's wrong the vast majority of the time.

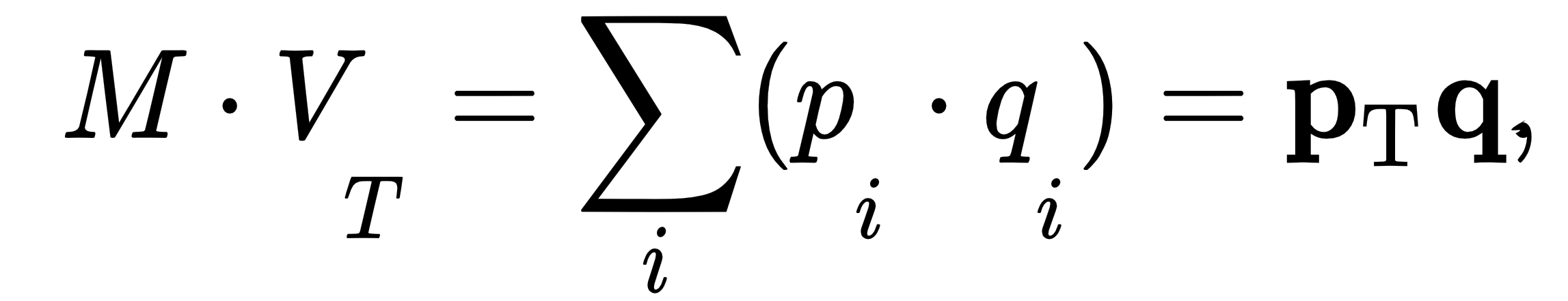

We begin with the uncontroversial transaction equation of exchange:

First, let's look into both sides of this accounting identity

- The left hand side is the product of total amount of money available and how often it circulates in the economy. It measures the flow of money in the economy by how much money circulates.

- M is the total amount of money in circulation - the money supply.

- V is the transactions velocity of money telling us how many a unit cost of money is used to pay for a good or service. The higher the velocity the more it circulates.

- The right hand side is the sum of all money spent across all transactions. It measures the flow of money via goods exchanged.

- p is the price of the ith good exchanged in the economy

- q is the quantity of the ith good exchanged in the economy

The equation states the amount of money spent in the economy is equal to the monetary value of the goods exchanged in the economy. This accounting identity is not the Quantity Theory of Money.

The Quantity Theory of Money takes this identity and makes some analytical assumptions which results in the theory that an increase in the money supply will increase the price of goods.

We begin by aggregating the right-hand side of the equation. Rather than summing every exchange of goods in the economy, we introduce the fourth price of money - P - as a variable into the equation. Likewise, we do so with the quantity of goods exchanged. We call this T - the total number of transactions in the economy.

We now look at the left hand side of the equation. We keep the money supply as it is. However, instead of looking at the transactional velocity of money, i.e. the number of times a unit of money is used in all transactions, we replace it with the income velocity of money, i.e. the amount of times money is used to buy final products or services (GDP) in the economy. This is denoted V.

This gets us the more infamous equation of exchange: MV=PT. The QTM asserts a direction of causality from the left hand side of the equation to the right hand side of equation, i.e. the money supply causes the price-level. The QTM assumes that the velocity of money and the number of transactions are equal. It also assumes that money is created exogenously by the central bank and then pumped into the system.

Monetarism, the macroeconomic monetary theory of Milton Friedman, stated precisely this. That if the central bank can merely control the money supply, then it will control inflation. At a time when stagflation was rampant in the West, Friedman's monetarists ideas offered a quick and simple fix. Alas, Friedman's monetarism is simply wrong.

Critique of QTM and Monetarism

Unfortunately, the Quantity Theory of Money and monetarism, for all its simplicity is wrong the vast majority of the time. In Part 2, we explored how money is not created exogenously by the central bank. Rather private banks create money when it expands both sides of its balance sheet issuing loans. Central banks simply the lacks the control over the money supply required for it to be a useful policy tool, and that's assuming QTM still holds true ... which it doesn't.

The problems with QTM begins when it assumes that the velocity of money and number of transactions in the economy remain constant. Both assumptions are false. The number of transactions in the economy will vary depending upon how the rate of profit in the economy regulates aggregate demand and aggregate supply. This should become clearer when we look at the transactional equation of exchange, in which we account for every transaction in the economy. This number will fluctuate over time. For instance, you can expect more grain transactions near harvest time and when the yield is fruitful than out of season. As you'll se later, the US monetary was prone to instability because around harvest time many wanted cash to purchase grain, which caused runs on banks.

As far the velocity of money, this is sensitive to expectation of how well the economy is performing and going to perform. If expectations are low, then money will be hoarded by those who can save which further dampens economic performance because money is not being invested in productive activity. John Maynard Keynes called this the paradox of thrift.

However, there are further problems for the QTM. First, it ignores the hierarchy of money. Some money is better than other money. Furthermore, there is n o hard distinction between credit and money. What we think as credit at one moment of time, can become money at another time. Likewise, what we think as money at a particular time, can become credit at another time.

We also alluded to the fact that substantially increasing the supply of high quality, high powered money into the system can cause inflation even if there is no increase in the money supply. This is because if we flatten the hierarchy, Gresham's law implies the distinction between good money and bad money becomes too blurred so all money becomes either bad to be used and spent, rather than hoarded; or is good to be hoarded, and not spent. Both have catastrophic consequences whether that be inflation, an asset boom, or a depression.

Once we accept the Hierarchy of Money, not merely as analytical tool for describing the monetary economy, but as an inherent and fundamental feature of the monetary system then the credibility of the Quantity Theory of Money vanishes into non-existence.