The Fundamentals of Accounting

Every financial transaction in the modern economy is a swap of IOUs— 'I owe you'. Exchanging IOUs - the swap - is the heartbeat of finance. The swap is the fundamental instrument underpinning all exchanges. We record swaps on balance sheets. Balance sheets enable us to record accurately and think rigorously about transactions in the economy. We represent a balance sheet using a Godley Table.

A Godley table consists of two columns:

- The left-hand side records assets

- The right-hand side records liabilities

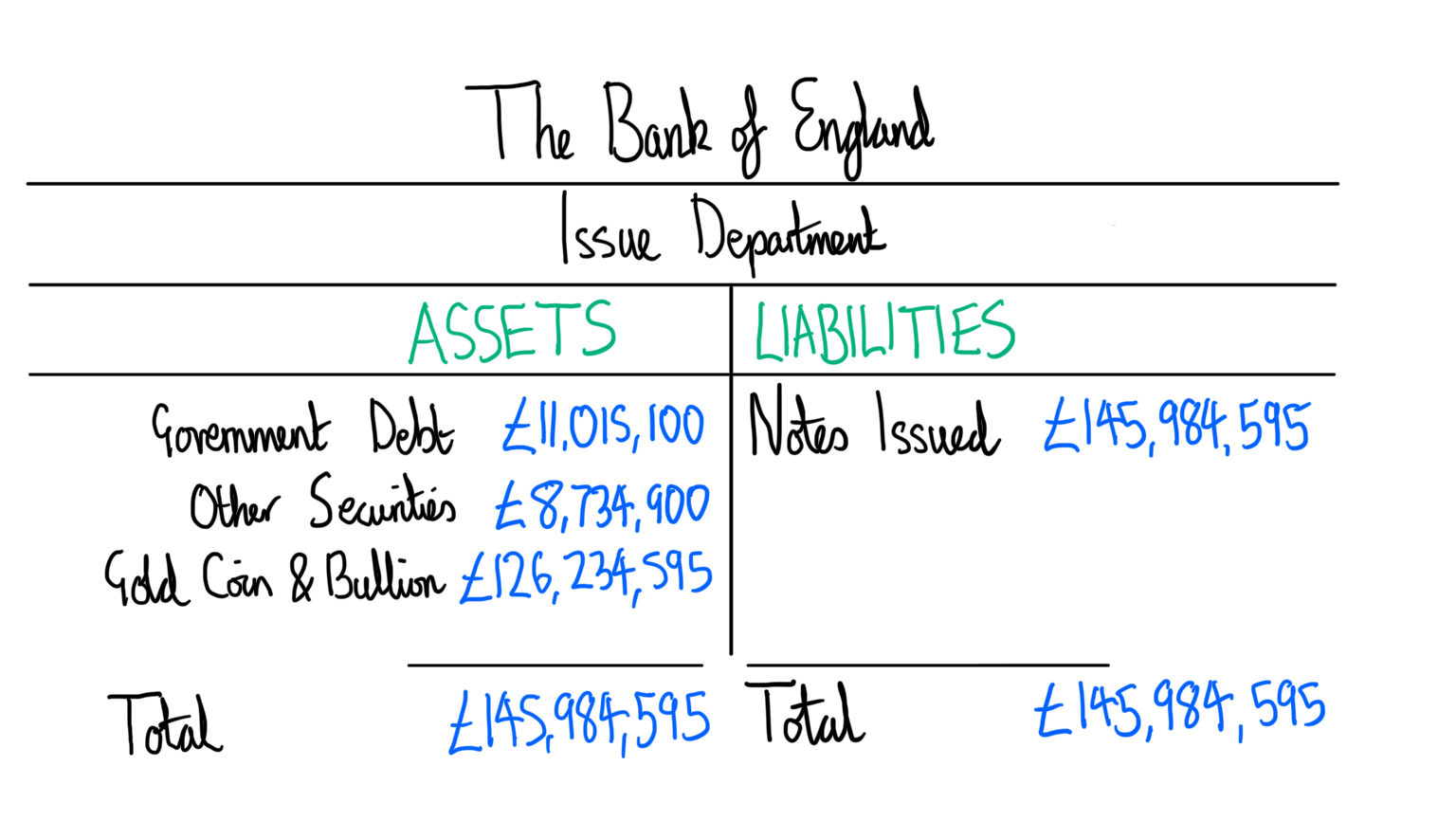

Figure 1, from Young (1999, p.308), presents the balance sheet of the Bank of England’s Issues Department from 1924. Even though it is old, it is a simple example of a real balance sheet. On the asset side, we find £126,234,595 in Gold Coin and Bullion. The asset side also includes Government Debt and Other Securities. On the liability side, however, we see £145,984,595 as Notes issued. Note both sides of the balance sheet are equal.

Rule: All accumulated balance sheets must balance. Suppose you add all the balance sheets of everyone and everything in the economy. Now sum all the assets and all the liabilities. At the end of it, assets = liabilities. That equation is true for the system as a whole.

For an individual balance sheet, we add a net worth to the formula to ensure they balance:

assets = net worth + liabilities (1)

This is the fundamental accounting equation which always holds true. Subtracting liabilities from both sides results in :

assets - liabilities = net worth (2)

The intuitive truth of equation (1) should now be apparent. If your assets ≥ liabilities, then you are solvent. If your liabilities > assets, then you are insolvent.

Just because you are insolvent does not mean you are bankrupt. Bankruptcy arises when you are unable to pay off your liabilities. Bankruptcy is a cash flow, or liquidity, problem. Liquidity is the ability to easily transfer one asset to another. When you have a liquidity problem, you cannot easily transfer one asset into another. Typically this means not being able to sell an asset for money so you can pay off your liability. During financial crises, liquidity problems force market agents to sell their assets at less than the value it was worth which can result in insolvency.

We call this double-entry bookkeeping. Every transaction appears at least twice in the system on the accounting books. If I gain money, someone gains my IOU. If I lose money, someone else loses my IOU.

The Mechanics of Finance.

Depositing Money: What Actually Happens

Let’s consider a simplified example: depositing £1 million in cash at a bank. We get to cosplay as an investor - Warren Buffett. The joys of being rich!

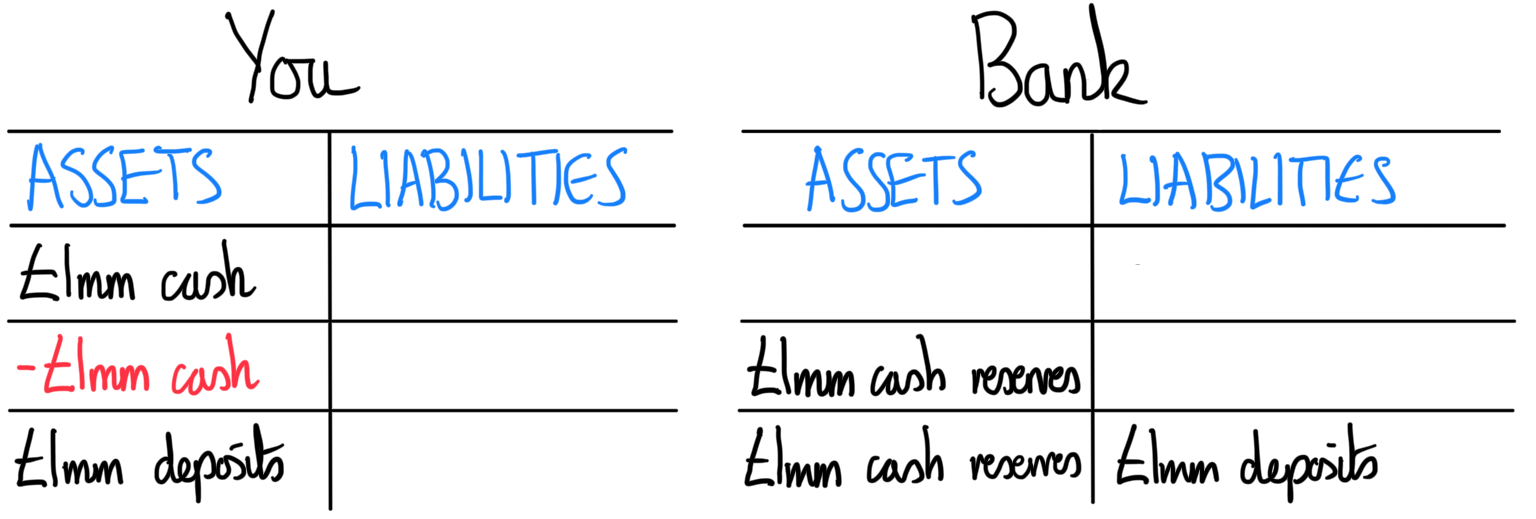

Here’s what happens:

- You begin with £1 million in cash.

- You give £1 million in cash to the bank.

- The bank adds the cash to its reserves and simultaneously creates a £1 million deposit account in your name.

At no point does the bank merely place the cash in a vault for safekeeping. It takes the cash as reserves and creates a deposit account of equal value. Ordinarily, when illustrating this financial transaction we would omit step 2.

By the end of this transaction:

- You’ve converted £1 million in cash/currency into £1 million of deposits. The size of your assets remain the same.

- The bank’s balance sheet has increased in size on both sides by £1mm.

- No one’s net worth has changed.

The Mechanics of Issuing a Loan

Now let's use this £1 million deposit to obtain a £10 million loan from the same bank. Let's also not forget that even though getting a £10 million loan would be like us getting a pay day loans, he wouldn't be so rich treating it so blasé.

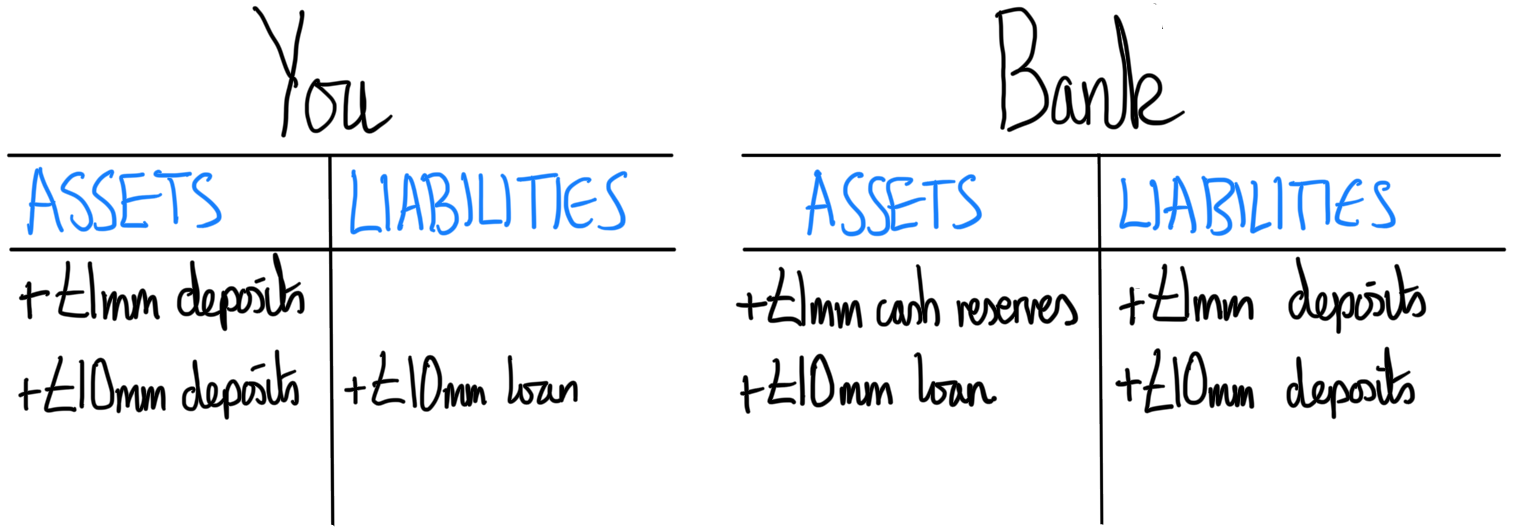

The first line merely tells us what we already know, that we've deposited £1mm in cash to the bank. On line 2, the bank creates the loan.

The key points are as follows:

- When the bank issues the loan, it expands both its and our balance sheets on both sides.

- Both ours and the bank's net worth remain the same

- An increase in purchasing power has occurred

- This is a great example of double-entry bookkeeping. On the bank’s side, the loan is a new asset—it expects repayment—and the new deposit is a liability. On your side, the new deposit is an asset–you can use it for expenditure, while the loan is a liability you will need to repay.

Bank of England home

Bank of England home

The deposit and the loan are simultaneously created by the bank. Neither existed before. Neither existed prior to this transaction. Through this action, the bank has created new purchasing power—it has literally generated money where none existed before. We call this endogenous money creation. This is the essence of how money is not merely transferred, but created through the process of lending.

Private banks create the overwhelming majority of money through demand deposits when they issue loans. This process generates new purchasing power without reducing anyone else's—a fundamental feature of the banking system. In doing so, banks create a circuit: a flow of money and credit that traces the new purchasing power throughout the economy until it is ultimately destroyed when someone repays the debt or settles a tax obligation, effectively closing the circuit. This framework is called monetary circuit theory, or circuitism for short.

Bank of England home

Bank of England home

There are important constraints to this process of creating money:

- A bank must expand both sides of its balance sheet when lending; it cannot simply create deposits without a corresponding asset.

- Regulations constrain banks. For instance, they are restricted from lending freely to those with poor credit.

- Reserve requirements apply retroactively—banks lend first, then meet reserve obligations later.

- Central banks influence lending via interest rates. They set the rate on unsecured overnight lending between banks. This rate acts as a floor on other lending rates. Examples include:

- The Fed Funds Rate (US)

- SONIA – Sterling Overnight Index Average (UK)

- €STR – Euro Short-Term Rate (Eurozone)

- Interest rates affect borrowing decisions, influencing aggregate demand for credit.

- Market forces shape bank behavior. Banks must lend profitably—otherwise they will go bust in the future.

- Risk is managed using tools like:

- Interest rate swaps (IRS), which hedge against fluctuating interest rates

- Credit default swaps (CDS), which insure against default

- Households and businesses may use new loans to repay old debts, influencing the rhythm of credit creation.

Even though in terms of balance sheet operations there is nothing stopping banks creating money at will, this inaccurately describes the reality. Banks ultimately must seek a profit when it issues a loan so it must account for whether the loan will be repaid or not. The economic necessity for extracting a profit, and not a loss, acts as an economic constraint for how much a bank can lend. Further regulatory constraints also impose restrictions on what the bank can and cannot do.

Investing Simplified

With this newly created purchasing power, Warren Buffett now wants to do his bit for the climate. He seeks to invest £10 million into the Green Hydrogen Enterprise, an innovative company that wants to use Hydrogen as a source for fuel from green energy sources.

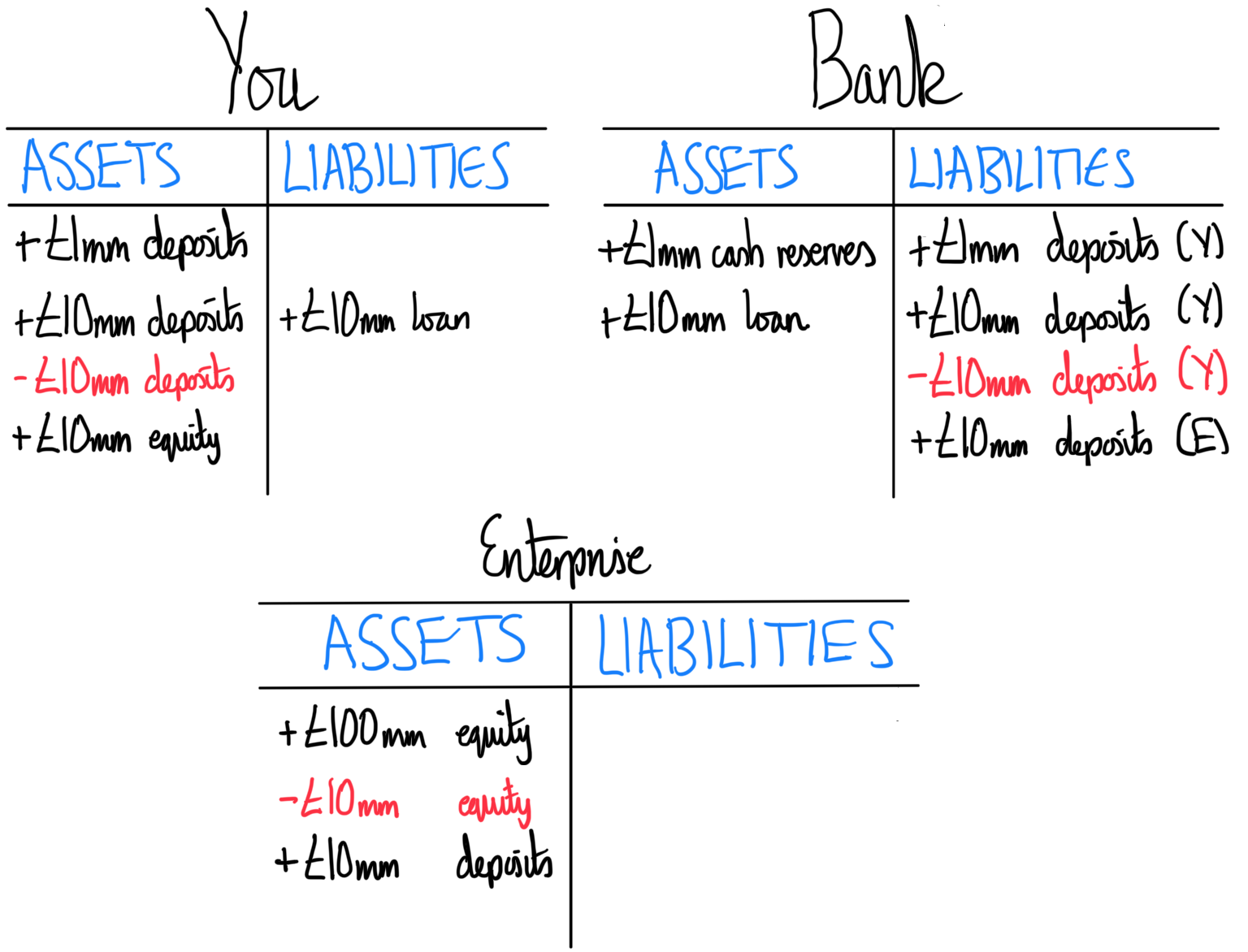

Let's analyse this slightly more complicated balance sheet. Lines 1 and 2 of both yours and the bank's balance sheet represent the previous examples.

On your balance sheet:

- Line 3 represents you subtracting £10mm in deposits to purchase equity in the Green Hydrogen Enterprise. In reality, the transaction would never be as simple as withdrawing £10mm from the account. Banks place limits on withdrawals above certain amounts without prior notice

- On line 4, you attain that equity. You still have £1mm in the bank deposit account. Assuming that you bought 10% equity for 10% control in the firm, you also now have 10% voting share in our company. You'll also receive dividends from the company.

In reality, such transactions are more complicated. Warren Buffett, you, could have driven a hard bargain and wanted £10mm for 25% control of the firm. Such a proposition if accepted, would either force the company to change its net worth from £100mm to £40mm, or existing stockholders would see reductions in their net worth as they sold stocks at below the asset value on their balance sheet. Depending on the size of liabilities, such a drastic drop in net worth would make the company, or stockholder, insolvent forcing it/them to trade on money markets to resolve this issue.

On the Green Hydrogen Enterprise balance sheet:

- Line 1 represents its initial starting equity, £100mm.

- Line 2 subtracts £10mm equity from the firm.

- Line 3 adds £10mm deposits ensuring the net worth of the enterprise remains the same.

On the bank's balance sheet:

- Line 3 removes deposits from your deposit.

- Line 4 adds them to corresponding Green Hydrogen Enterprise deposit account held at the same bank. All the bank has done is change who it is liable to. It has no change in net worth.

In reality, financial transactions are far more complex. We’ve assumed both parties use the same bank. If they didn’t, the bank would need to transfer reserves to another institution. If it had insufficient reserves, then it would need to acquire them on money markets by borrowing from other banks, redeeming liabilities, or borrowing from the central bank. For the sake of this essay, we don't need to concern ourselves with these complex but real world examples. We simply need to understand the accountancy principles and how Godley tables help us think rigorously about the transaction.

The Limits of Alchemy

As already noted, in practice banks cannot create money at will. Both economic and institutional restrictions apply constraining its power in creating money. The biggest constraint of all is that a bank must expand both sides of its balance sheet when creating money. Both an asset and liability must be created. Consequently, all bank money is inside-money and it can never create outside money, i.e. money that is an asset to everybody and no one else's liability. Money is created so that it can be subsequently destroyed when liabilities are paid off reducing the bank's balance sheet on both sides.

In circuit theory, the act of creating money and a corresponding liability creates a circuit. When money is used cancelling that liability, the circuit ends. When the circuit for a particular transaction ends, we say that a payment has been settled or funded.

The principal aim of banks is creating purchasing power and markets in order that they can earn a profit for that service. This imposes an economic constraint on the bank. Profitability is key for the survival of the bank and enabling it to invest elsewhere, or absorb losses due to risk it incurs. Every lending operation involves the bank taking on risk which if not considered properly can undermine the bank's balance sheet and its solvency. Without confidence in a return, banks will only reluctantly lend.

Regulatory requirements are also imposed on banks. Such regulations are designed to ensure the stability of the banking system and the economy as a whole. They are also designed to prevent fraud and financial abuse. Ultimately, the state decrees that banks are allowed to create money in the same denomination as the currency of said state. This legitimises both the authority of the state, via indirectly protecting the state's influence, and the bank who issues money on par with currency, at least in terms of price. The result is a hybrid system in which private banks are granted very powerful tools in shaping the economy, in return for accepting the state's authority.

In Money: A Prolegomena - Part Three, the final part of this series, we'll delve into the core concepts of analysing money from a macroeconomic perspective.